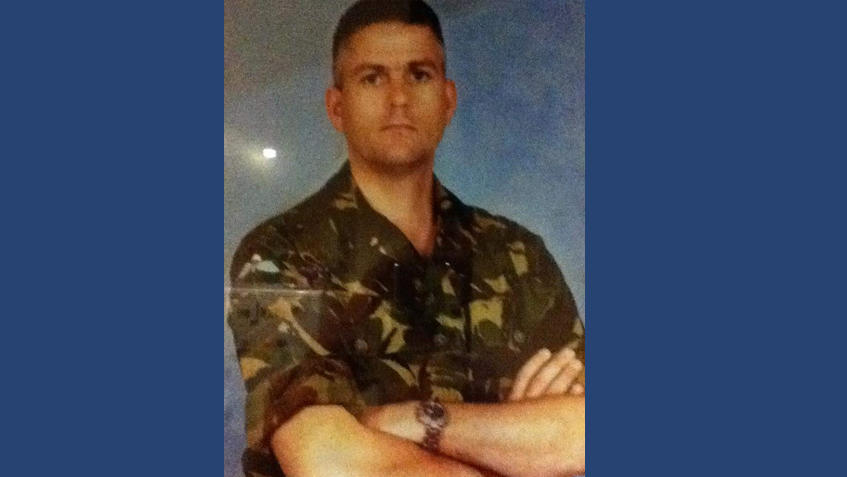

Stuart Moore

Stuart Moore had just turned nineteen when Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands. When he and his brothers, all Royal Marines, were called back to barracks in April 1982, they assumed they were off to Scotland. Instead, they boarded the SS Canberra and began the 8000-mile journey into the South Atlantic, unaware of how the coming months would shape and shadow their lives for decades.

"Without going too much into it," says Stuart, "If it wasn't for help, I probably wouldn't be here.

The Royal Marines were always on Stuart's mind. He was thirteen when he decided he wanted to join. He passed for duty in April 1980, was deployed to the Falklands in 1982, and served for a total of 24 years. Having kept a tight lid on his feelings throughout his life, it was only after he retired in 2003 that things began to "bubble up.”

Stuart was finding "the lid would flip off" and his memories would land him in very, very dark moods. His mood swings could be triggered by "anything really," he says, "smells, sounds, memories, voices, names… anything." It was his wife - "very much my leveller"- who told Stuart something wasn't right. He agreed to see a doctor, "and that was, you know, some time ago" - the first step on the long road to finding effective treatment.

Throughout his service, Stuart had been immersed in what he describes as "a very masculine organisation, a very tough bunch of chaps" - where therapy wasn't on the menu. "It wasn't something that was offered, it wasn't something that you would look for," he says.

Interestingly, he suggests service itself can mask an underlying problem: "You don't think it hurts so much because you are still in that organisation. You have your friends and you laugh and joke, you know, you have very dark humour, so it's a norm. It's not until you leave, you know…”

This military connection, the rapport and shared language, was key in the end to Stuart's successful treatment. After being "batted around a bit" between different charities, he was struggling to make a connection with a civilian therapist. "I suppose I was looking for military help," he says.

He finally found it, when a friend mentioned PTSD Resolution. When Stuart made the call, he had his first therapy session arranged within the week: "The chap who came to see me was ex-military," he says, "so there was a mutual understanding. Being able to talk about things… you don't have to explain military terms and military humour. You can just say it to a Veteran and he or she will understand - because they have the same phrases. I found that so much easier."

"Talking helps," Stuart says, "I am a believer in that now" - but his aversion to asking for help was strong. "I wouldn't do that," he says of his former self, "because it would be a sign of weakness, and I don't like that sort of thing.”

In many ways, the Falklands conflict marked a turning point in the way military trauma was talked about and understood. Amongst, arguably, the first cohort of service people who have been encouraged to discuss and confront their combat experiences, Stuart is representative of a wider cultural shift.

"One of the lessons to be learned from the Falklands experience," says PTSD Resolution Chairman and CEO, Colonel Tony Gauvain (Retired), "is that no matter how stiff the upper lip may be, and how well any reminders are avoided or denied, the neurological reality is that traumatic memories remain in the brain as part of the human survival mechanism, to trigger the necessary emotional response when threatened.”

"Treatment reduces that sensitivity to a less volatile level.”

Stiff upper lips may be on the wane but British understatement is not. When asked if he is in a better place after therapy, Stuart says, "Well, I'm still here.”

"I'm sure my wife is grateful for that. Sometimes. When the bins need taking out. But no, it's a positive, a positive outcome for me - and for my family. They still have me.”

His reticence - and his resilience - is evident as he considers the upcoming anniversary of the Argentine surrender on June 14th. "I don't do anniversaries really," he says, "I never have.”

I remember incidents, battles, losing friends… But no, it's just another day.”